ETL 1110-1-175

30 Jun 97

without bound as the lag increases, a regionalized

random variable with a linear variogram will have

ever-increasing variability about its mean as the

size of the sampling region is increased. In appli-

cations involving the linear variogram, the vario-

gram is usually truncated at a sill corresponding to

the value of the variogram at maximum lag hmax.

g. Before closing this section, it will be use-

ful to highlight some similarities and contrasts

between the covariance function and the vario-

gram. Although the variogram is commonly used

in a geostatistical analysis, it is sometimes easier to

gain an intuitive understanding of the methodology

using the covariance function, or equivalently, the

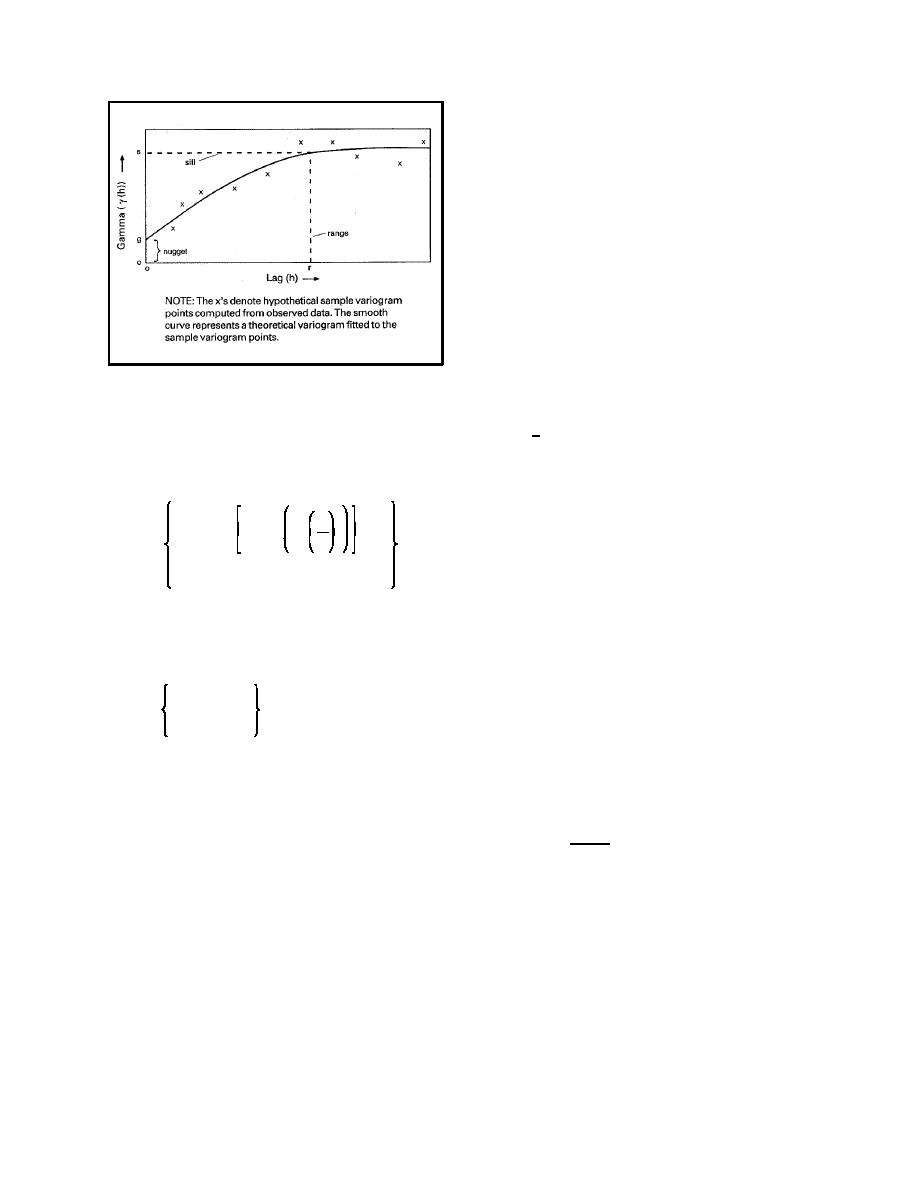

Figure 2-2. Diagram showing variogram and features

spatial variance and the correlation function.

When Z(x) has a stationary, isotropic covariance

the Gaussian variogram (parameters: sill, s > 0;

function (Equation 2-9), there is a one-to-one

nugget, 0 < g < s; range, r > 0)

correspondence between the variogram and the

covariance function, namely

2

h

(2-27)

( (h) = C (0) & C (h)

, h>0

g % (s & g) 1 & exp &3

( (h) =

(2-25)

r

As long as C(h) approaches zero as h increases (a

h=0

0,

minor technicality that can always be assumed in

practice), then, as indicated by Equation 2-27, the

and, the linear variogram (parameters: nugget,

variogram reaches a sill and the sill equals C(0).

g > 0; slope, b > 0)

Therefore, when dealing with a covariance-

stationary regionalized random variable, the vario-

g % bh, h > 0

gram and the spatial covariance function contain

(2-26)

( (h) =

the same information as one another. By factoring

h=0

0,

out C(0)=s from Equation 2-27 and using Equa-

tion 2-14, the relationship between the spatial

f. Although there are many other models that

correlation function and the variogram can be

are used for variograms (Journel and Huijbregts

obtained

1978), these four are the most commonly used and

are shown in Figure 2-3. The exponential, spheri-

( (h)

D (h) = 1 &

(2-28)

cal, and Gaussian models are similar in that they

s

all have a sill and a range. However, they have

different shapes near zero lag (h=0) that, as will be

From Equation 2-28, it is evident that high values

discussed in Chapter 4, result in significant differ-

of ((h) (i.e., close to s) signify low values of D(h).

ences in the prediction results using the three

In fact, D(h) = 0 whenever ((h) = s, indicating that

models. The linear model is quite different from

observations whose locations are farther apart than

the other three, in that it does not reach a sill, but

the range are uncorrelated. As h gets small, a

increases linearly without. This fact will have

nugget in ((h) is reflected in a correlation that is

important implications on the prediction results

less than 1

using a linear variogram. Because the squared

differences between residuals tend to increase

2-8

Previous Page

Previous Page