ETL 1110-1-175

30 Jun 97

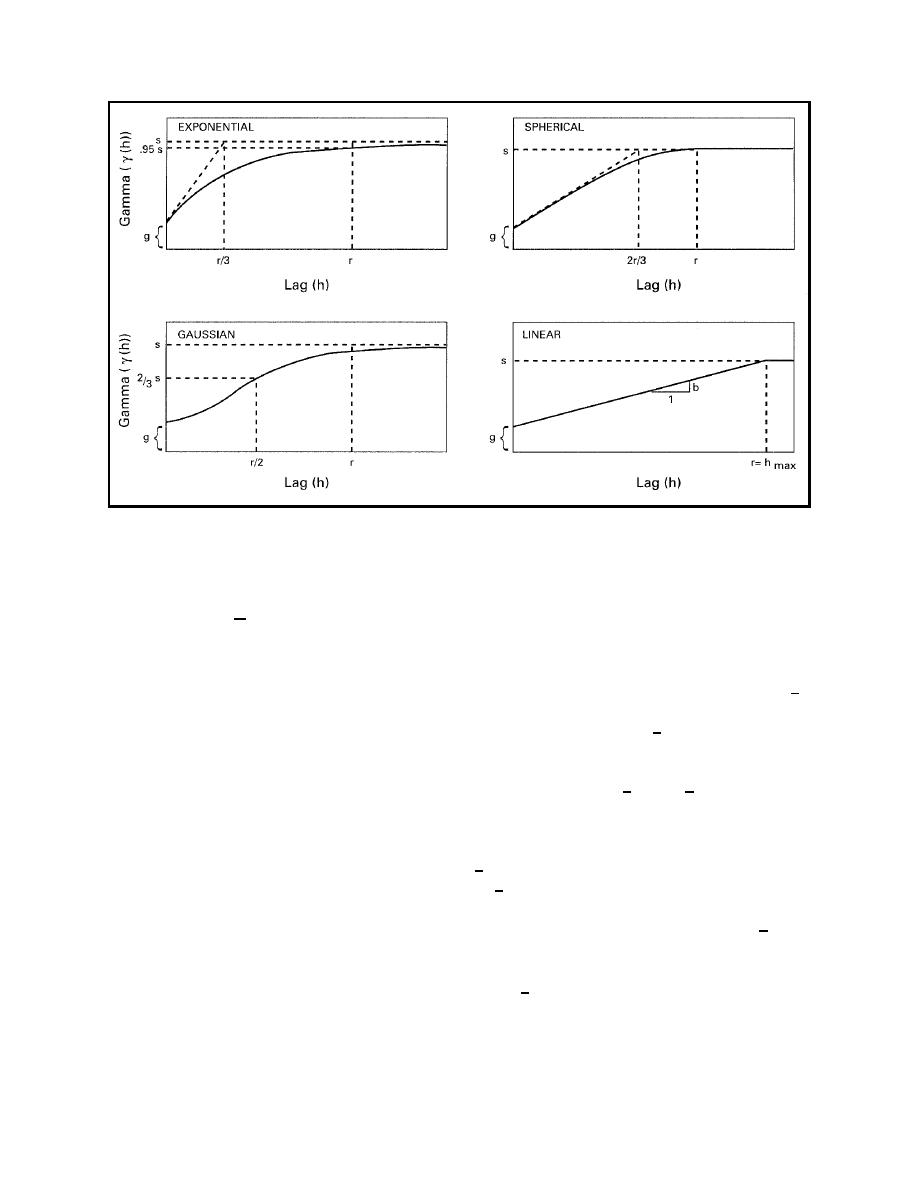

Figure 2-3. Theoretical variograms showing A, exponential; B, spherical; C, Gaussian; and D, linear

models

61&

60

2-4. Kriging

g

D (h)

(2-29)

as h

s

a. General.

Therefore, the larger g is in relation to s, the less

(1) Given a regionalized random variable Z(x)

correlated nearby observations are. The case when

with a known theoretical variogram, the question

g=s, called a pure nugget variogram, results in

is: how can the value of Z(x) be predicted at an

D(h)=0 for all h>0. In that case, neighboring

arbitrary location, based on measurements taken at

observations are uncorrelated no matter how

other locations? Suppose that Z is measured at n

closely they are spaced.

specified locations: Z(x1), ..., Z(xn). For example,

h. Occasionally, ((h) may not reach a finite

the locations might correspond to n preexisting

sill, as in the linear variogram Equation 2-26. In

wells in an aquifer. Let a new location be given by

that case, it is not possible to define a correlation

x0=(u0,v0) and denote the ith measurement location

function as in Equation 2-28. The corresponding

by xi=(ui,vi). Suppose that, based on prior knowl-

regionalized random variable is said to be intrinsi-

edge of the geology, there are no prevailing trends

cally stationary (Journel and Huijbregts 1978),

in hydraulic conductivity, so the mean of Z(x) is

which is more general than covariance stationarity.

assumed to be constant over the entire region:

The theory behind intrinsically stationary vario-

grams will not be presented in this ETL. As long

(2-30)

as a "pseudo-range" hmax is defined, all of the

(x) = (constant)

computations described below can be generalized.

2-9

Previous Page

Previous Page